Wednesday, October 18, 2006

Way Back Wednesday

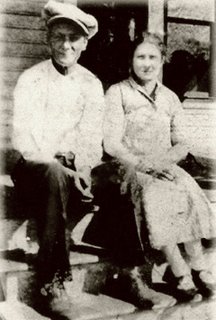

This weekend is my Nana's family reunion. This is a picture of her parents David Andrew Kilgore, and Ida Lillian (Pritchett) Kilgore, taken on their first house in Dublin, Georgia, this was their house that burned down. Since the reunion is this weekend, I've finished a scrapbook for everyone to see, and been working on their genealogy. This is what I have on David Andrew Kilgore's grandfather, Elijah Kilgore.

ELIJAH KILGORE

Around 1816 ELIJAH KILGORE was born in Tennessee to parents who had migrated there from Virginia. It has been suggested that Elijah might be the son of Steven Kilgore of Virginia, and a descendant of one of the Kilgore brothers who fought at King's Mountain in the Revolutionary War. All of us who are researching Elijah are working hard on that one.

Around 1835, Elijah married NANCY E. KNIGHT, daughter of JONATHAN & ELLENDER KNIGHT of North Carolina. The marriage date is approximate. I checked for a marriage record by letter written April 14, 1986 to Pikeville, TN, even though the courthouse burned in 1908. Nancy gave birth to their first son on July 26, 1836, in Pikeville, Bledsoe County, Tennessee, and they named him JOHN JACKSON KILGORE. Then came CHARLES KILGORE around 1839 and ISAAC CALVIN L. KILGORE in April of 1840. With his family growing, Elijah apparently began looking around for a homestead. There was a lot of unclaimed land at that time, and the government was selling it cheap. On October 27, 1841, a survey was done in Elijah's name for 500 acres. It wasn't until seven years later that Elijah was able to claim the property on April 15, 1848, probably due to not having the money to pay all the fees attached to such grants at that time.

In a note to me from Tennessee Archivist III, Marylin Bell Hughes, on Nov. 17, 1993, she writes: "There was a great deal of land in Tennessee when we became a state. After North Carolina was allowed to grant land for service in the Revolutionary War, there was still a lot of land left. In 1806 Tennessee obtained the right to grant land (first deed to property) in its own right. Land was cheap as the state officials wanted to bring more people in to populate the land and to pay taxes. Therefore, some fees were attached to the land office procedures. A fee was paid to file the entry, to file the survey and to file the grant. Over the years the legislature added additional time spans to pay off these debts. However, sometimes the individual did not pay the fees and lost the ability to obtain the grant (deed). It would appear that your ancestor did not pay a fee at the given time but he may have been allowed further time to pay it. This must be the case as he later obtained the grant. Hopefully this explains the questions which you pose."

Shortly thereafter the family moved on and set up house in Bradley County, a section of Tennessee which had been reclaimed from the Indians only 14 years before. By 1850, the Kilgores were firmly established landowners in Bradley County and the proud parents of seven children: John, Charles, Calvin, James, Ellender, Elijah Taylor, & Nancy Emma.

What caused the Kilgore family to move yet again is unknown at this time, but on September 22, 1855, Elijah bought 160 acres in Catoosa County, Georgia, from George M. McCully. In the 1860 Georgia census, Elijah, Nancy and nine of their 11 children were enumerated. Charles and Isaac Calvin were missing, probably working on a farm somewhere away from home, since they still lived.

A year later, the first shot of the Civil War was fired and changed the lives of the Kilgore family forever. Isaac Calvin Kilgore was mustered in on 10 Jan 1862 in Dalton as a private in the 12th Georgia Cavalry, Company A, Avery's Squadron, Georgia Dragoons. His horse was valued at $175. Two months later John Kilgore enlisted on March 4, and James followed four months after that. Both John and James were privates in Company F, 39th Regiment, Georgia Volunteer Infantry, Army of the Tennessee. Charles also enlisted, but I have yet to find his record. More about Charles later.

The records are spotty on all the brothers, but what records have been discovered show Isaac was captured March 28, 1863 at Pulaski, Tennessee. There is a family story of Isaac escaping from captivity by hitting a guard over the head. Here is the story as told by Ruby Tennessee Kilgore: "Union soldiers had him imprisoned in a cotton house when it came up a real bad storm and the guard at the door came inside. Uncle Ike acted like he was having convulsions and passed out. When the guard turned around, Uncle Ike hit him in the head with his boot." Records from the military prison in Louisville, [KY] show Isaac being captured less than a month later in Murfreesboro, Tennessee on April 14 1863 and shows him as a private in the 4th Regiment Georgia Cavalry. According to records from Camp Case, Ohio, Isaac C. Kilgore was listed on a role of prisoners claiming to be deserters, transferred from Louisville on May 4, 1863. Such a claim may have led to his early release. According to his release papers from Camp Case, Ohio, Isaac was 5'10" tall, of light complexion, with light hair, blue eyes, and was 21 years old. He was released May 27, 1863 upon signing the oath of allegiance. (The story of the escape has gotten confused with 2 brothers over the years, but the record here seems to indicate that Ike was the one).

If I'm reading the records correctly, both James and John were in a unit that never made it to the end of the war. Their regiment was one of two with Danville Ledbetter defending Chattanooga against Mitchell. Both James and John Kilgore fought at Chattanooga, Shiloh, Champions Hill (also called Baker's Creek), and the Siege of Vicksburg. (It seems that John may have fought later with another unit, according to the Confederate Census form he filled out). This regiment was under fire so often it was almost completely wiped out. All remaining living men deserted before the end of the war. The last of them jumped off a troop train and headed for home. In all, this regiment had marched some 3,320 miles, about one-fourth of them barefooted. James was captured at the Siege of Vicksburg on July 4, 1863, and was paroled in Vicksburg on July 15. On August 25 he deserts the army and is on the run. On October 18 John deserts and goes within Federal lines at Sale Creek, TN. He is received at the military prison at Louisville, Kentucky on November 12. The next day he takes the oath of allegiance and is released to remain north of the Ohio River for the duration of the war. It is my opinion that many of the men from Vicksburg later went over to federal lines because they were starving. I say this because the soldiers of Vicksburg, being under siege, were on half rations, the non-combatants even less. (Food for the Confederates was always scarce at the best of times). The diets inside the besieged city was supplemented in some cases by mule meat and rats. They were shelled day and night, the only breaks coming when the federal guns were cooled and reloaded. The Confederate men dug holes in the hillsides for the women and children as a haven from the shelling, but became a matter of honor among the men not to go into them.

Back at home, not only do the Yankees take over the town of Ringgold, but the Battle of Chickamauga is fought practically in their backyard. (There is a story of Jeff Kilgore, a toddler at the time, hiding under the bed while the battle was going on). John and James fought in the defense of Chattanooga and the Kilgore home is repeatedly subjected to surprise searches by Union soldiers looking for the Kilgore sons. On one such surprise search, a Union soldier jabbed under a bed with his bayonet and yelled, "I got one! I got one!" Mother Nancy came near to collapsing thinking one of her sons had sneaked in during the night. It turned out the soldier had run his bayonet through a pumpkin that had been stored under the bed. One of the sons, probably one too young to be in the war, had a favorite pony, which he tried to hide. But "the Yankees found it anyway," the story goes.

Yet life goes on, even in war. Their daughter Ellen (Ellender), married a rock mason from Ireland, Ralph Adams, in 1862. By 1864, Elijah and Nancy are the proud grandparents of little Mary Adams, born during the long last days of the Civil War. (There may have been some births before Mary, but, if so, those have not yet been found).

However, not all the stories have quite the good ending as the one which turned out to be a pumpkin. As the war wound to a close, the Kilgores gathered at the old homeplace for an anticipated reunion. Probably among the group were the new daughers-in-law, Sarah Jane Doster & Elmira Ellis, who married Isaac Calvin & James during the war. Stories from several family sources say that Charles Kilgore was making his way home. He had come as far as the path leading to the house and was nearly home when shots rang out from ambush. When the smoke cleared, Charles Kilgore lay dead, shot in the chest and in the head. The family heard the shots and ran down the road, where they found Charles lying with one hand across his forehead and the other over his heart. This story has been handed down through two different lines of the family and was also told to me by Ethel Langford Simmons, Theodosia Kilgore's granddaughter. The story was also heard by Janice Murphy through Theodosia's son, Willie Edward Gillihan).

As the years passed, the "swords were hammered into plowshares", and the soldiers went back to the land. Elijah and Nancy were blessed with their children's families living clustered around them. Five years after the war, only William Frank, age 18; David Andrew, age 15; and 13-year-old Theodosia still lived at home, and the family had just had another wedding. This time their oldest son, John, an old bachelor of nearly 34 years, married 22-year-old Emiline "Emma" Parker.

Elijah Kilgore, not content with just farming, also became an itinerant preacher, traveling over much of Lookout Mountain in Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee. The Kilgores must have entertained many distinguished guests at their home because young Theodosia, (or Doshie, as she was called), remembered serving at the table for these serious-minded people. Everything was so quiet the sound of their munch, munch, munching was all that could be heard. It was too much for young Doshie, who found it hilarious and broke into uncontrollable giggles. (I doubt that sat very well with those solemn guests and her father).

As the decade of the 1870's wore down, so did the light of their family, Mother Nancy. Having weathered a war and the death of a son, Nancy did not make it to her 60th birthday. It was probably just after her mother's death that Theodosia went to visit her sister, Ellen, who had married and moved away from Georgia, in Carbon County, Wyoming. It was there she lost her heart to a man with long, elegant mustaches by the name of James (Thomas?) Madison Owens. (I have a picture of him). They marry, though he is not popular with her brothers. The story goes that he "sounded different" which might have meant a foreign accent which sounded Northern to those struggling through the aftermath of the Civil War. James Owens was born in Ireland in 1844, according to an old family Bible in the possession of the late Ethel Simmons, Theodosia's granddaughter.

Elijah, now a widower, found solace with a woman 19 years younger. Her name was Teresa A. Inman, and on September 15, 1878, they were married in Whitfield County, Georgia. Two months later, his youngest daughter, Theodosia, gave birth to a son, James Madison "Jim" Owens, Jr. It is not known exactly what happened to the Kilgore family after Elijah's second marriage, but by 1880, all the children had left home; some had left the state. David, Jeff, Theodosia and her two children were living in a house together in Catoosa County. Theodosia's baby, Lillie Augusta Owens, was barely two months old. (Lillie was my great-grandmother). I believe there was a rift in the family after Elijah remarried, whether on the part of his new bride, Teresa, or on the part of his grown children, is not known. Elijah became a father again in October of 1881. They named the little girl, Ida Lee Kilgore. Elijah was 65 years old. When Ida Lee was about 11 years old, her father's health began to decline and he made his Last Will and Testament. Everything was left to his wife Teresa, and, in the event of her death, to his 11-year-old daughter, Ida Lee. Apparently, Jeff Kilgore, who married in 1882 to Tennessee Rinkle, owed his father some money, because in the will Elijah said:

"With respect to my worldly estate, I give and bequeath to my loving wife Terressa all of my lands and household furniture and such money as may be in my house at the time of my death, and all of my stock and farming implements with proviso that if my son Jefferson pays my wife Terressa $150 in six years after my death, then my wife must make Jefferson's son a good and sufficient title to 80 acres lying on the east side of my home, lot #76, and further bequeath that at the death of my wife Terressa, all of the foregoing property to descend to my daughter, Ida Lee Kilgore. If Jefferson fails to pay the $150, then in that case the title is to remain in my wife Terressa [Terressa's] name."

On April 28, 1891, Elijah Kilgore died in the North Georgia mountains of Catoosa County where he had lived the last 37 years of his life. There is a story that has survived in the family and told to me by two people unknown to each other. The story goes that, as Elijah lay dying, he told his family that he would die at midnight. Some of his sons decided to set the old clock back one hour, hoping to keep him going a little longer. But, as the clock struck the false hour of eleven, Elijah commented that "something is wrong; it's time for me to go." And he died at midnight exactly when he said he would.

Elijah was about 75 years old when he died. He was born in Tennessee when it was still wilderness. He was working his land when the Union troops took possession of Ringgold and used it for their headquarters. Somehow, he, his family, and his farm survived and flourished. By the time of his death, the Kilgore farm boasted cows, sheep, hogs, horses, wagons, farm implements, and good household furniture. But the farm did not survive after Elijah, for, unlike the hour of his death, the future would not be as he envisioned it. His wife Teresa apparently died either just before, or just after, Elijah, and the land and all possessions went to the 11-year-old child, Ida Lee. A couple of months later, all household items, livestock, and farm implements, were sold, many of them bought by the Kilgore sons. No one knows why all 11 of Elijah's children by his first marriage were left out of his will. For several years, the farm itself must have lain fallow unless it was rented, because it wasn't sold until 1905 when it was bought by L.L. Parker of Hamilton County, Tennessee, possibly a relative of John Jackson Kilgore's wife, Emaline Parker.